It is late afternoon. The city is still warm. A body pauses before deciding where to sit.

The bench is narrow. The edge is hard. The posture feels predetermined. Sitting means sitting upright, facing forward, for a limited amount of time. Lying down is not allowed. Leaning is uncomfortable. The body adjusts, shifts, negotiates.

In that brief moment of contact, before any building or street comes into focus, the city is experienced through posture. Through touch. Through the surface that receives the body. The Living Chair emerges from this perception.

The chair as an architectural question

The question posed by the international competition The Architect’s Chair (Buildner) seems simple. Architects have designed many chairs. Especially within modern and contemporary architecture, the chair has been a recurring object of experimentation, from iconic designs to more speculative ones. It almost feels inevitable that an architect, at some point, will design a chair.

This fascination is not accidental. The chair is the most complex piece of furniture to design. More than a table, more than a shelf, more than a lamp, the chair demands an intimate negotiation with the human body. It must respond to posture, weight, balance, rest, and movement. It must consider ergonomics, but also habits, cultures, and different ways of inhabiting the world.

The first skin that surrounds the body is clothing, and then comes the chair. The next would be the room. As a surface that receives the body, the chair operates as architecture at its most immediate scale, where form meets the exact dimension of the human body.

This understanding was already present in some of the earliest modern furniture designed by European architects, particularly German and Dutch designers. Figures such as Mart Stam, Mies van der Rohe working with Lilly Reich, and Marcel Breuer presented their work at the Weissenhof Siedlung housing exhibition in 1927, during the interwar period. Through these experiments, new materials were introduced, and metal became a central medium for rethinking furniture design.

And yet, while architects have designed many chairs, there are surprisingly few chairs in the city conceived with this same care. Even fewer pieces of urban furniture have been designed starting from the body. Cities are full of benches, edges, and places to sit, but most assume a single posture, a single duration, and a controlled way of occupying space.

The urban chair as landscape

We decided to take the competition opportunity to design an urban chair, conceived as a furniture-landscape: an inhabitable surface and an infinite line capable of operating as urban furniture.

Unlike interior furniture, which has advanced through innovations in ergonomics and materials, urban furniture has remained largely static and uniform. As both Be Seated by Laurie Olin (2017) and The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces by William H. Whyte (1980) show, the design of seating directly shapes how public space is occupied, perceived, and valued.

The Living Chair emerges from this decision. Not as an isolated object, but as urban furniture that can exist both inside and outside. Not as a fixed form, but as something closer to a landscape: a surface that can be inhabited in multiple ways, individually or collectively, briefly or for extended periods of time.

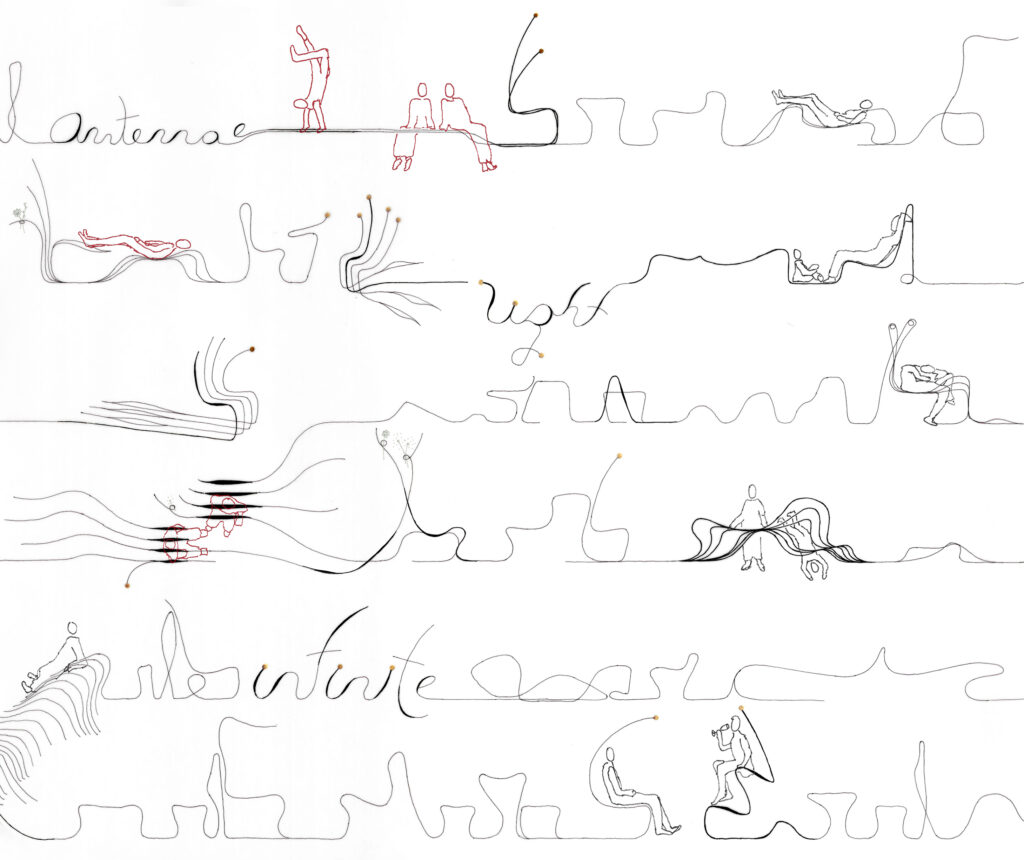

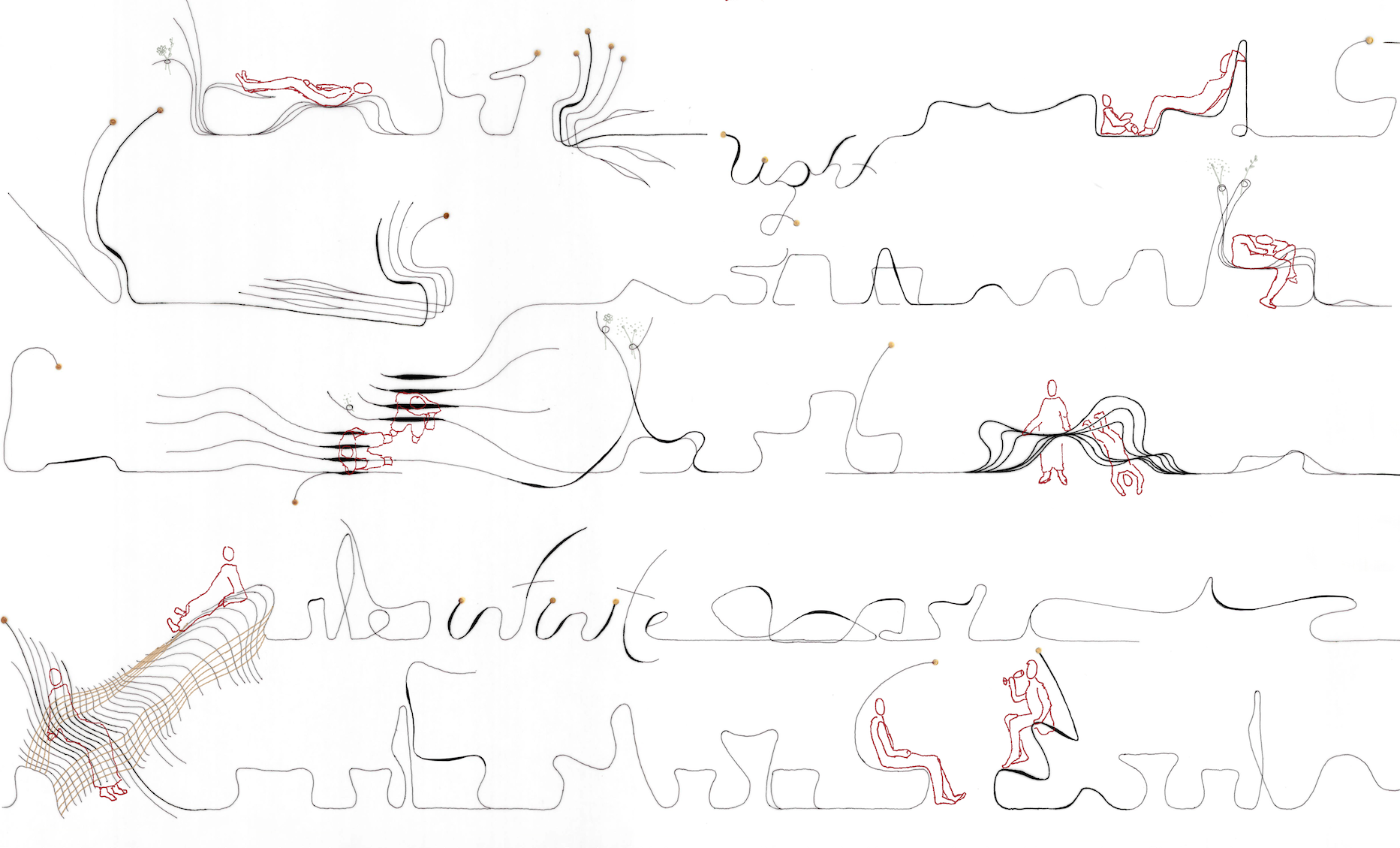

The Living Chair is conceived as a living system, an infinite and adaptable structure that unfolds like a continuous line. Almost like a piece of calligraphy drawn in space, it reaches the ground, rises, bends, expands, and contracts. It does not prescribe a single posture. Instead, it offers a wide range of bodily possibilities: sitting, leaning, lying down, gathering, playing with children, socializing, flirting, resting, reading, observing. The chair adapts to what the body asks for, not the other way around.

As urban furniture, the Living Chair supports both individual and collective use. It allows bodies to approach or distance themselves, to sit together or apart, to share space without obligation. It can be inhabited alone or in groups. Like a furniture landscape, it accommodates different ages, rhythms, and intensities of use.

Materiality as a living organism

Materiality is central to the Living Chair. When looking at chairs designed by architects throughout modern history, a recurring logic appears: structure and skin, skeleton and surface, support and contact.

This distinction is already present in many modern chairs. In the work of Marcel Breuer, or in the furniture designed by Mies van der Rohe together with Lilly Reich, structure is clearly exposed. These chairs are almost anatomical. They reveal how a body is held, where weight is distributed, and how material becomes support.

A similar logic appears in the Chaise Longue designed by Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, and Pierre Jeanneret, where the body is carefully studied and accommodated. Here, furniture is not decorative. It is conceived as an extension of the body, responding to rest, gravity, and comfort. These chairs acknowledge that furniture is always about posture and care.

The Living Chair builds on this lineage, but shifts it toward the urban and the temporary. Its structure is conceived explicitly as both skeleton and skin. The skeleton is imagined as a biodegradable or recyclable resin structure, with a bone-like appearance. Varying in thickness, it provides both structural integrity and bodily comfort.

Wrapped selectively around this skeleton is a woven skin, ideally made from biomaterials such as fungal mycelium or banana fibers. This skin does not fully enclose the structure. It appears only in specific areas, like tissue around bones, enhancing comfort and inviting touch. It is translucent, slightly sticky, flexible yet resistant, responding to pressure and movement.

Over time, this skin could biodegrade, disappear, or merge with the surrounding environment. Furniture here is understood as temporal rather than permanent, evolving rather than fixed. The Living Chair behaves less like an object and more like an organism, adapting to use, climate, and time.

Form, calligraphy, and body awareness

Beyond materiality, the Living Chair is deeply informed by form as a bodily and spatial experience. The chair is not conceived as a closed object, but as an infinite line, capable of continuous transformation. This idea comes from understanding form not as something fixed, but as something that unfolds in relation to the body.

A key reference is Verner Panton’s Visiona 2 (1970), an immersive interior landscape in which furniture, architecture, and body dissolve into a single continuous environment. In Visiona, seating is no longer discrete. It becomes terrain. The body does not sit on an object but inhabits a space. This idea of furniture as landscape strongly influenced the Living Chair.

Another important reference is Verner Panton’s Multi-Level Lounger (1964), where the chair abandons the idea of a single correct posture. Instead, it allows multiple bodily positions: reclining, leaning, stretching, sitting halfway, or lying down. The chair adapts to the body, not the opposite. This freedom of posture is central to the Living Chair.

The Living Chair also relates to non-Western ways of inhabiting the body. In Japanese culture, sitting on the floor, such as in seiza, introduces a different relationship between body, ground, and furniture. Chairs are not always elevated objects; sometimes they are surfaces, gestures, or minimal interventions. In this sense, chairs can also be understood as cultural artifacts, not only ergonomic devices.

This understanding connects to the idea of chairs as art, where furniture moves beyond function and becomes an expression of bodily awareness. The Living Chair embraces this ambiguity. It is functional, but it is also experiential. It invites the body to explore, adjust, and choose.

The continuous line of the Living Chair is also inspired by the calligraphic drawings of León Ferrari. In Ferrari’s work, line escapes legibility and becomes movement, density, accumulation, and tension. His calligraphies are not meant to be read, but visually traversed. They suggest infinity, repetition, and variation.

The Living Chair adopts this logic. Its form behaves like a calligraphy drawn in space: a line that can thicken, loosen, overlap, rise, descend, or open itself. This allows multiple forms of inhabitation to emerge without prescribing a single use or posture. Body awareness here is not imposed; it is discovered.

Sensoriality, light, and care

The Living Chair is conceived as a sensorial experience. It is not only about how the body sits or rests, but about how the body feels, perceives, and becomes aware of its surroundings. Sensoriality here is not an added layer; it is fundamental to how the chair operates in the city.

Light plays a central role in this sensorial dimension. The Living Chair incorporates small, movable, solar-powered lights, conceived as subtle extensions of the structure, almost like antennas. These elements are not decorative. They respond to practical needs while simultaneously shaping perception, atmosphere, and orientation in public space.

Light allows the chair to be used at night. It supports reading, waiting, resting, or simply being present in the city after dark. At the same time, it introduces a sense of safety without resorting to harsh or excessive illumination. The light is soft, localized, and intimate. It does not flood the surroundings; it gently marks presence.

These luminous elements reinforce the idea of the Living Chair as a living organism. Like sensitive appendages, they respond to context, time of day, and use. They signal that the chair is active, occupied, and welcoming. Light becomes a quiet indicator of inhabitation, a way of saying that someone is there, without exposure or surveillance.

At certain moments, the continuous line that defines the Living Chair also thickens or opens, creating small cavities that can hold flowers or plants. This gesture is inspired by Kazuyo Sejima’s Hanahana Vase, where a simple opening allows living elements to appear and change over time. In the Living Chair, these moments remain secondary to light, offering an additional layer of softness and interaction without defining the project.

Care, in this sense, is not understood as protection through restriction, but as attention to the body and its needs. The Living Chair does not prevent certain behaviors; it supports multiple ones. It does not discipline the body; it accompanies it. This approach contrasts with much contemporary urban furniture, which often incorporates defensive or exclusionary design strategies.

By prioritizing light as a sensorial and spatial tool, the Living Chair proposes a different relationship between urban furniture and the body: one based on comfort, awareness, and trust. The chair invites presence rather than surveillance, intimacy rather than exposure.

From body to city

The Living Chair does not stop at the scale of the body. While it begins with posture, touch, and sensorial awareness, it inevitably extends into the city. The way bodies sit, rest, or gather in public space directly shapes how the city is experienced and shared.

Urban furniture is often understood as secondary to architecture, but in reality it plays a crucial role in defining how public space is inhabited. Furniture mediates between the individual body and the collective environment. It can invite lingering or encourage passing through. It can foster encounter or enforce distance.

In this sense, the Living Chair aligns with projects that understand furniture as an urban mediator rather than a decorative object. A relevant reference is the public space furniture designed for the plaza of Casa da Música by OMA, where seating elements are integrated into the ground and the landscape of the plaza itself. There, furniture is not added afterward; it is part of the spatial structure that allows people to sit, wait, observe, meet, and rest in different ways.

The Living Chair operates in a similar way. It does not impose a single use or posture, nor does it dictate how long the body should remain. Instead, it allows for different forms of occupation to coexist: solitude and encounter, movement and pause, play and rest. It acknowledges that public space is shared by bodies of different ages, abilities, rhythms, and emotional states.

This is particularly important when thinking about intergenerational use. Children may climb, play, or lie down. Adults may sit, talk, read, or wait. Elderly bodies may seek comfort, support, and stability. The Living Chair accommodates these differences without separating them. It does not assign zones or functions. It simply offers a surface that can be inhabited in many ways.

There is also a dimension of intimacy in this approach. Public space is often designed at a distance from the body, prioritizing visibility, control, and circulation. The Living Chair introduces moments of closeness, softness, and attention at a small scale. It allows the city to be experienced not only as an infrastructure, but as a place of care.

At the same time, the project preserves a sense of wonder. The chair-landscape is not entirely predictable. Its form invites curiosity and exploration. Bodies discover how to sit, lean, or lie through use. This openness recalls a childlike way of inhabiting space, where interaction is guided by intuition rather than instruction.

By working at the intersection of furniture, landscape, and urban space, the Living Chair suggests that urban regeneration does not always require large-scale interventions. Sometimes, it begins with small gestures that transform how bodies relate to the city. The project proposes an urbanism that is not monumental, but attentive; not rigid, but adaptable; not abstract, but deeply embodied.

Hand drawing as a way of thinking

The Living Chair ultimately proposes a different way of thinking about urban furniture and public space. It does not seek to solve a problem or to define a single correct use. Instead, it opens a field of possibilities, where the interaction depends on the physical, emotional, and mental state of each inhabitant. It is never the same chair twice.

By working at the scale of the body, the Living Chair suggests that awareness in the city begins with contact. Before buildings, before infrastructures, before masterplans, there is posture. There is touch. There is the simple act of sitting, resting, or leaning, and the way these actions shape our perception of space and of others.

In this sense, the Living Chair aligns with my broader interest in care, play, and dignity in public space. It resists the logic of control and efficiency that dominates much urban furniture today, and instead proposes softness, adaptability, and trust. It allows the city to be inhabited slowly, attentively, and with curiosity.

The final provocation of the project was to submit a hand-drawn A1 drawing to an international competition in the era of artificial intelligence. The drawing was not intended as nostalgia, but as a way of thinking through the body. Drawing by hand allowed the form to remain open, imprecise, and responsive, much like the chair itself.

The Living Chair is not an object to be consumed, but a condition to be inhabited. A chair-landscape that moves from the body to the city, proposing a more intimate, playful, and caring way of being together in urban space.