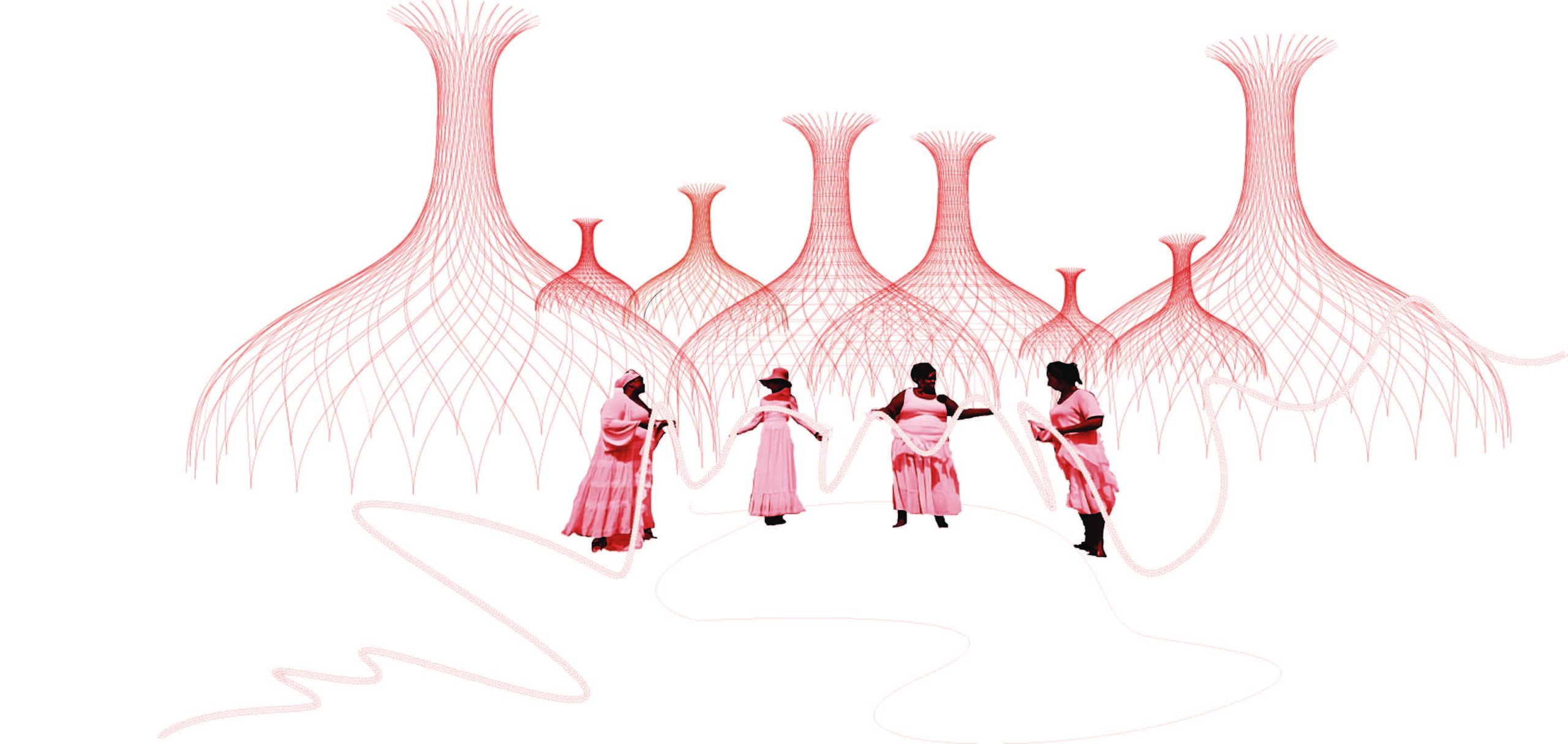

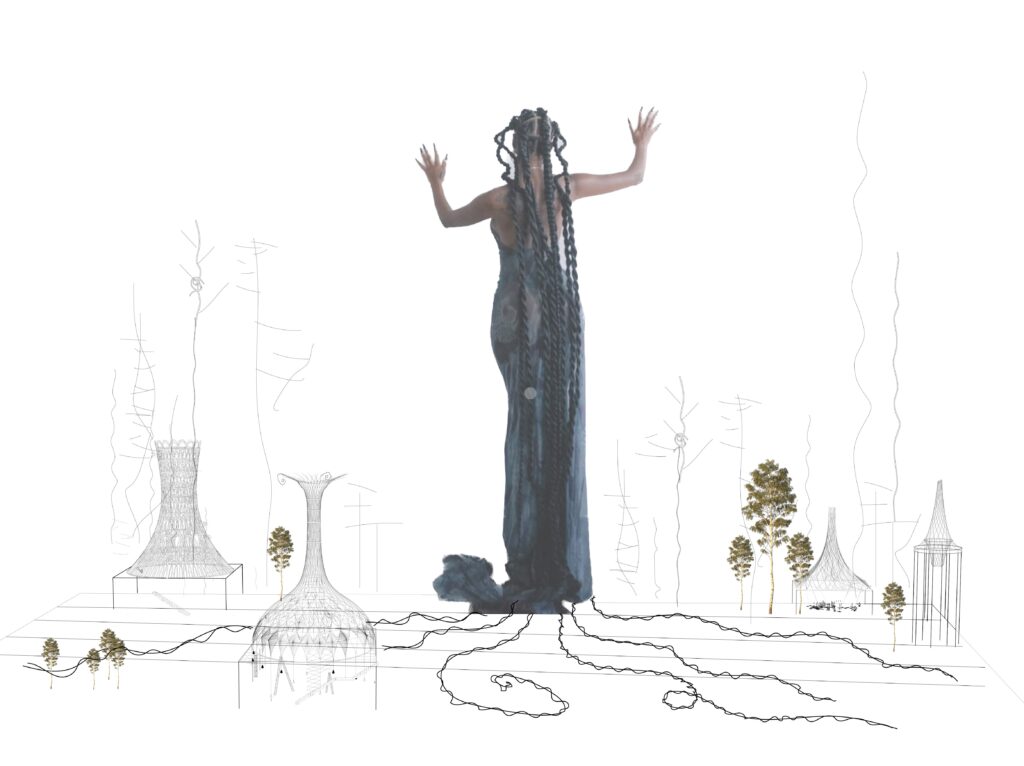

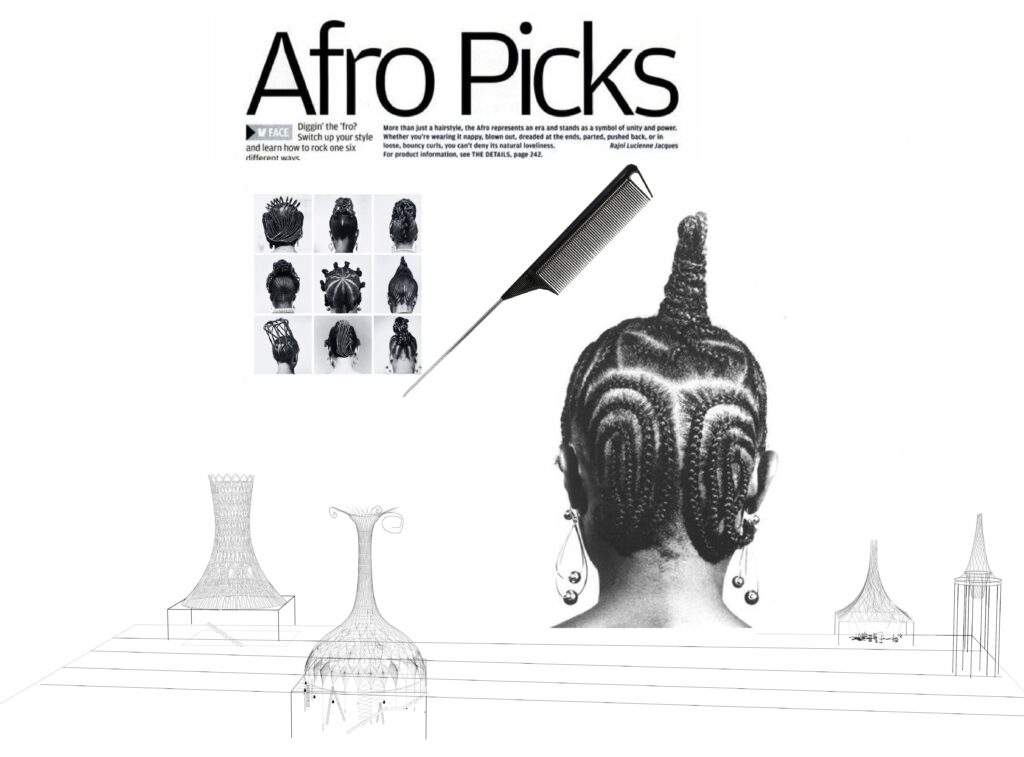

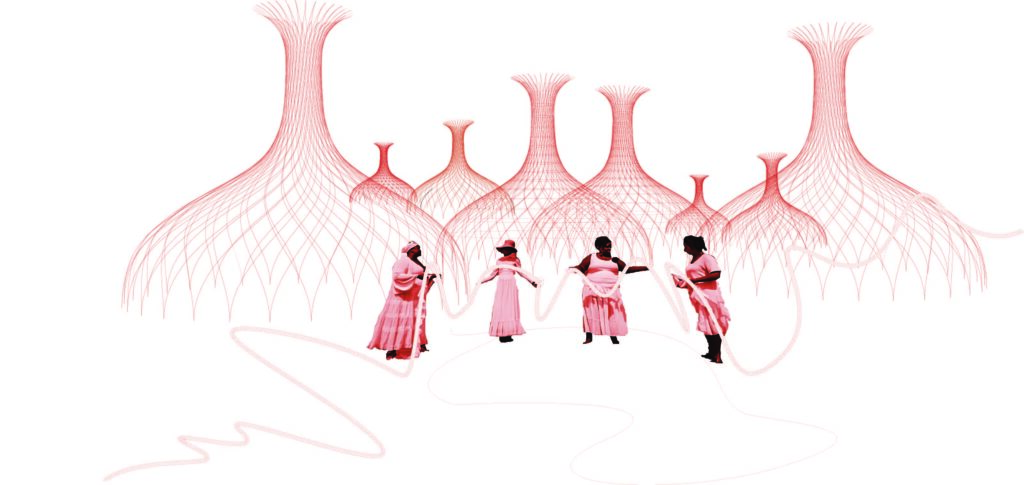

In July of 2020, amid a global pandemic and just after George Floyd’s murder, I found refuge from a grim news cycle in The Hair Styles Series documenting the powerful architectural spaces shaped with the braided and threaded hair re-popularized by Nigerian women in the 1960s and 70s and photographed by J.D. Ojeikere as Nigeria emerged from British Colonial rule. Contemplating the row of black and white photographs curated from the Hair Styles Series, I first saw rooms — atriums, theaters, chapels — and then whole buildings emerging from the collection. Stepping backwards to view the hairstyles together, they became cities with office towers and houses, cathedrals, and markets. Working at the scale of the body, the hairstylists were “architects” conceiving and shaping whole new worlds through Blackness itself. In the process, they were revealing the agency of Black women — through their indigenous knowledge of natural black hair and its care practices — to disrupt the inequalities propagated through the constructed world, mitigate a warming climate, and re-imagine the world in their own image to meet their specific needs and desires.

The structural/spatial capacity of natural Black hair demonstrated in The Hair Styles Series is possible because Afro-textured hair has a coiled structure that allows it to resist the force of gravity and grow upwards from the scalp. Afro-textured hair evolved as a shelter for the body – the first space humans inhabit. In Sub-Saharan Africa, from which all of humanity arose, hair evolved as helix-shaped coils that not only protected the scalp from the intense heat across the African continent but also lifted the hair slightly above the scalp allowing sweat to evaporate and cooling the scalp the process. The coiled strands of Negroid (Black) hair give it a unique plasticity, allowing it to be sculpted into a myriad of forms and making it a compelling source through which to conceive new kinds of building materials.

I was particularly attuned to the architectural visions formed by the Nigerian hairstylists because I had spent the previous spring semester with my architecture students designing an intervention to transform a laundry mat into a “libro-mat” for the Single Mother’s Residential Program at the public art project, Project Row Houses, in Houston’s historic African American Third Ward community. The libro-mat, a combined laundry and library, allowed mothers to engage in literary activities with their children while also doing laundry. By happenstance, George Floyd grew up in public housing in Houston’s Third Ward, which birthed not only Floyd, but also Beyonce and Solange. The community is in many ways a microcosm of the richness of Black community and culture as well as the unique challenges — from environmental racism and climate change to red-lining and food deserts — confronting Black and brown communities and inhabitants such as Floyd. These complex, entrenched, and interconnected issues demand a more expansive, collaborative, and imaginative understanding of what architecture can be and do — perhaps an architecture based on Indigenous Black female knowledge could be enlisted to create new kinds of spaces to meet the unique needs of the Black community and adapt to an increasingly precarious environment. The unique Black hair texture, more than any other genetic trait, signifies Blackness, and its hair care practices have been a vibrant, living inheritance throughout African diasporic cultures for a millennium. An extension of the Black body, natural Black hair remains at the center of dialogues on power, cultural value, beauty, and social standing. It is a compelling tool to engender conversations on the meaning of Blackness as a cultural, intellectual, and aesthetic force.

Houston, May 28, 2024