Every line drawn is political. Whether drawn by a politician or an architect or an urban planner, the line defines the space. It designates certain individuals to inhabit the spaces it creates.

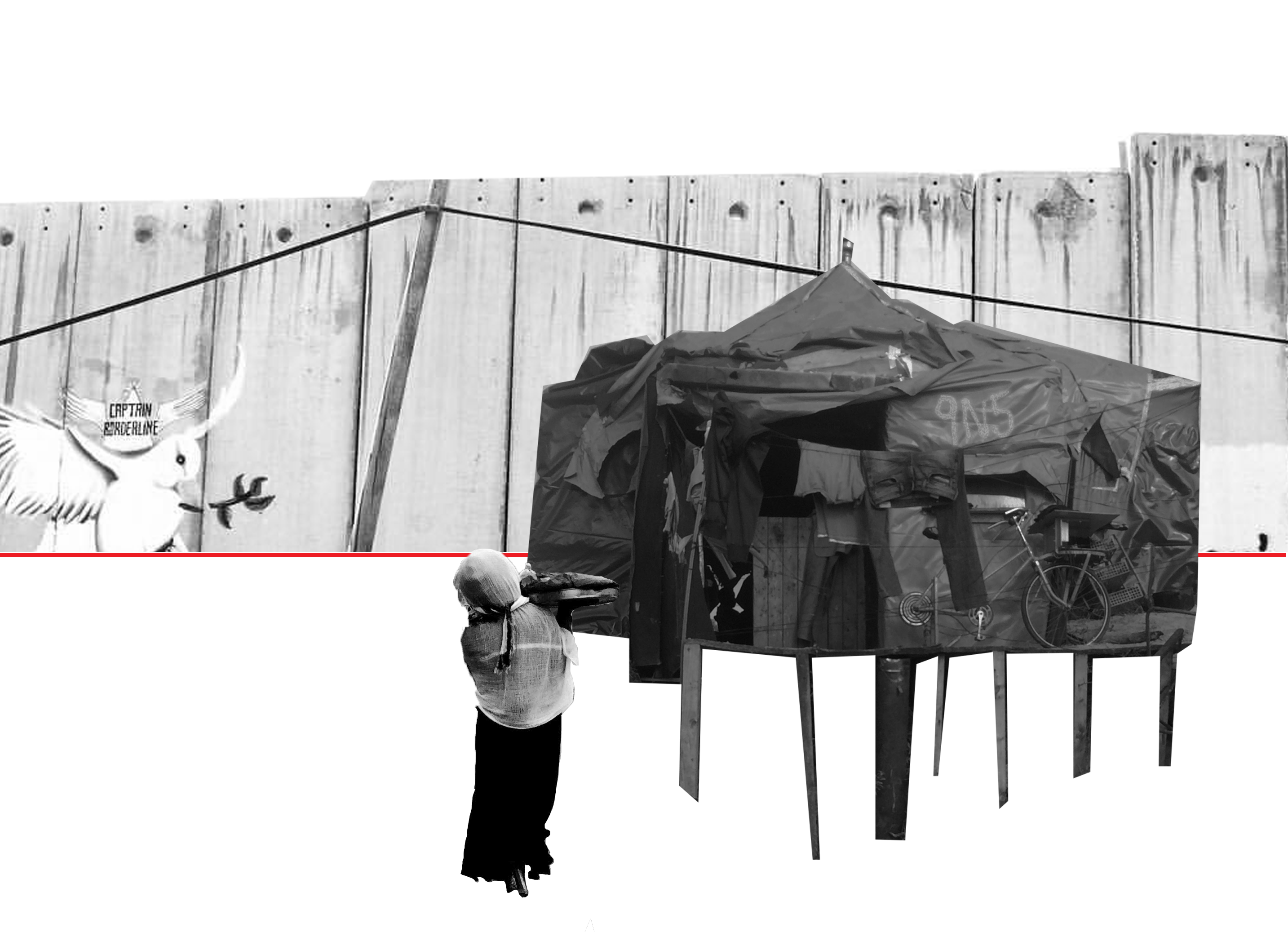

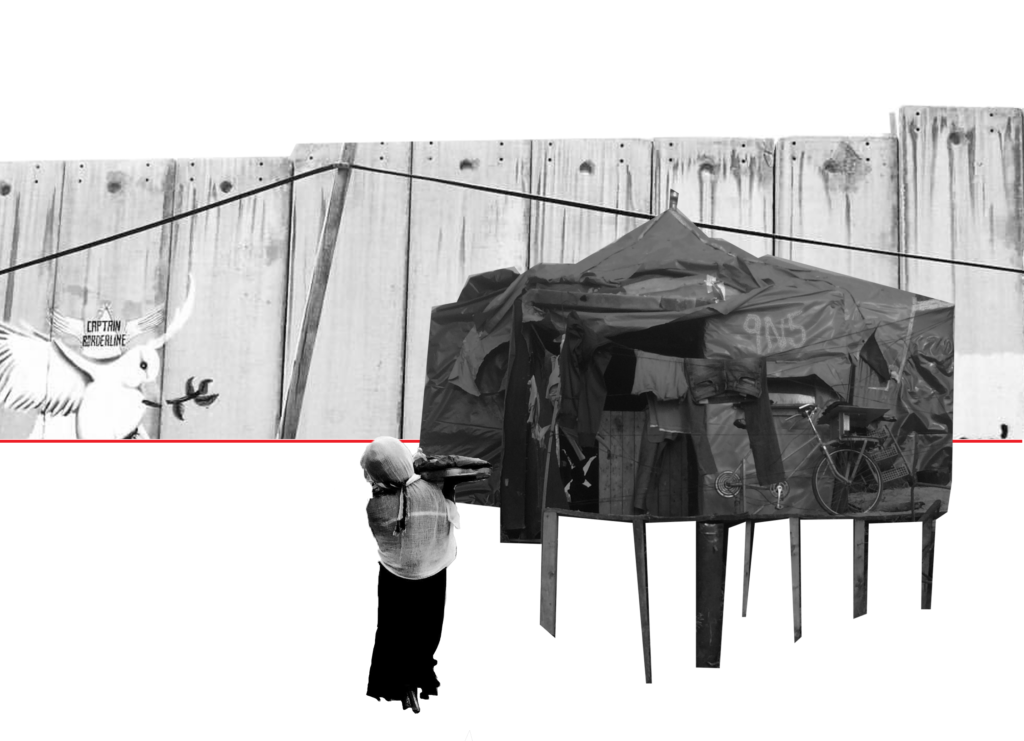

Borderlines around the world define spaces. They designate certain individuals to inhabit the spaces they create. These borders are transitional spaces that have immense impact on migrant and refugee memory. Is it the architect’s responsibility as a citizen of the world to 1) identify and acknowledge their complicity in the circumstances and conditions that lead to mass displacement, and 2) actively confront, call out at every scale, and propose alternatives against those institutional forces that lead to mass displacement? The physicality of the border and the design of temporal spaces calls into question the physicality of peace. Should we preserve these transitional spaces and transform negative space into positive architecture, and if so, what does this conservation look like? Perhaps our steel and concrete barriers can become greenways and parks. Perhaps these lines could become shared and adaptable spaces that citizens from both sides can inhabit.

Every migrant’s journey is different. Through an architectural lens, the migrant inhabits different spaces: a home from their country of origin, a detention center, a tent, varied transitional housing, a border, social housing, potentially a new home, etc. To analyze migrant architecture is to analyze ephemeral spaces like camps, detention centers, border crossings and transitional social housing, as well as defensive architecture and the architecture of war. Architecture transforms the void to urban, junkspace to active form, becoming the antonym of bigness, the epitome of architecture. The migrant or refugee lives in a realm of nomadic existence until reaching the unknown coordinates of a foreign land, their memory of origin still existing physically and mentally.

Temporal social housing can integrate migrants and refugees into urban communities. However, does this built environment assimilate foreigners to encourage cultural anonymity? Transient housing has the potential to embrace diversity and reflect its inhabitants, but often, identities are not considered within the design process of these temporary spaces. Participatory design addresses culturally appropriating these spaces. e.g. Muslim migrants placed in housing with windows facing out towards the public negate the intrinsic nature of separating public and private spaces within the home, ignoring religious gender divides, privacy and autonomy. Designing adaptable spaces that account for the individuals’ needs, as well as diversity in function, allows the inhabitants to actively participate in designing their home.

But how long will refugees and migrants reside in their host countries? We must take into consideration what countries destroyed in war will look like and what will exist in their place of destruction. The potential to modernize the memory of the people that once called those spaces home lies in the hands of governments, private entities and parties of interest ready to capitalize on destruction. To modernize the memory of war-torn countryside is to value fiscally participatory design; it is to engage with refugees to rebuild what existed using modern technology as a tool to honor the past of a given place. Is this optimism realistically feasible and fiscally possible?

Analyzing the spatial journey of a migrant allows the architect, as social activist, to observe transient architecture and define its scope with migrant communities. Possible solutions include designing physical spaces for peace manifestations, preserving heritage in post-war countries and culturally appropriating social housing for refugees and migrants.

Culture, religion, politics, sexuality, nationality and ethnicity both effect and affect how people occupy space. The migrant as a physical individual culture and ambition, brings with them a physical entity into a space, inherently altering any space in which they exist. Migration inevitably then redefines urbanity culturally, politically, economically and physically. There is now an urgency to redesign our cities through a humanistic approach that takes migration influx into consideration. Revitalizing the social urban through collaborative efforts with migrants would transform our public spaces to embrace everyone. Designing, thus, becomes an active political process, drawing the lines people occupy, making the future of memory physical.

Dallas, September 16, 2020