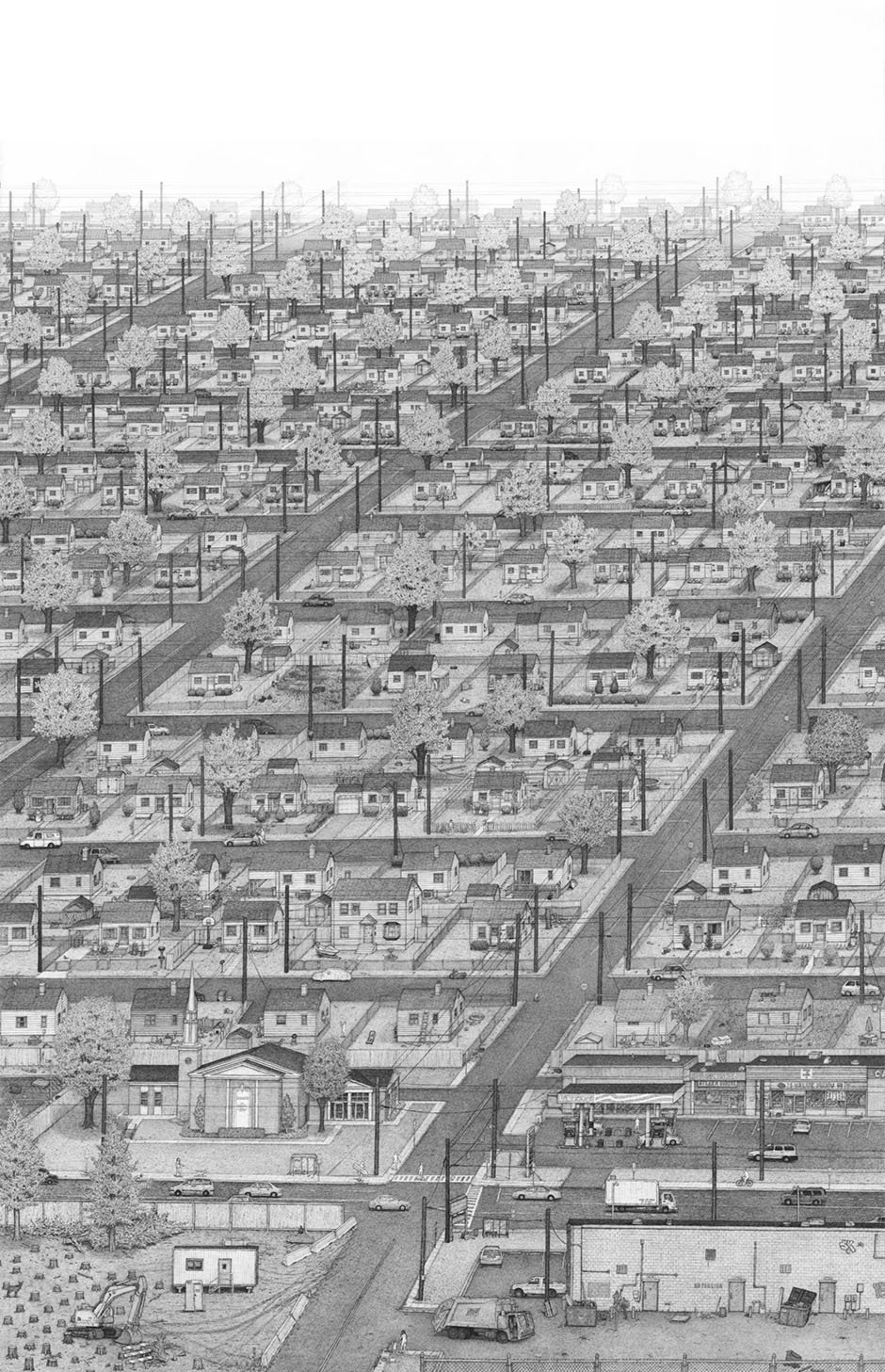

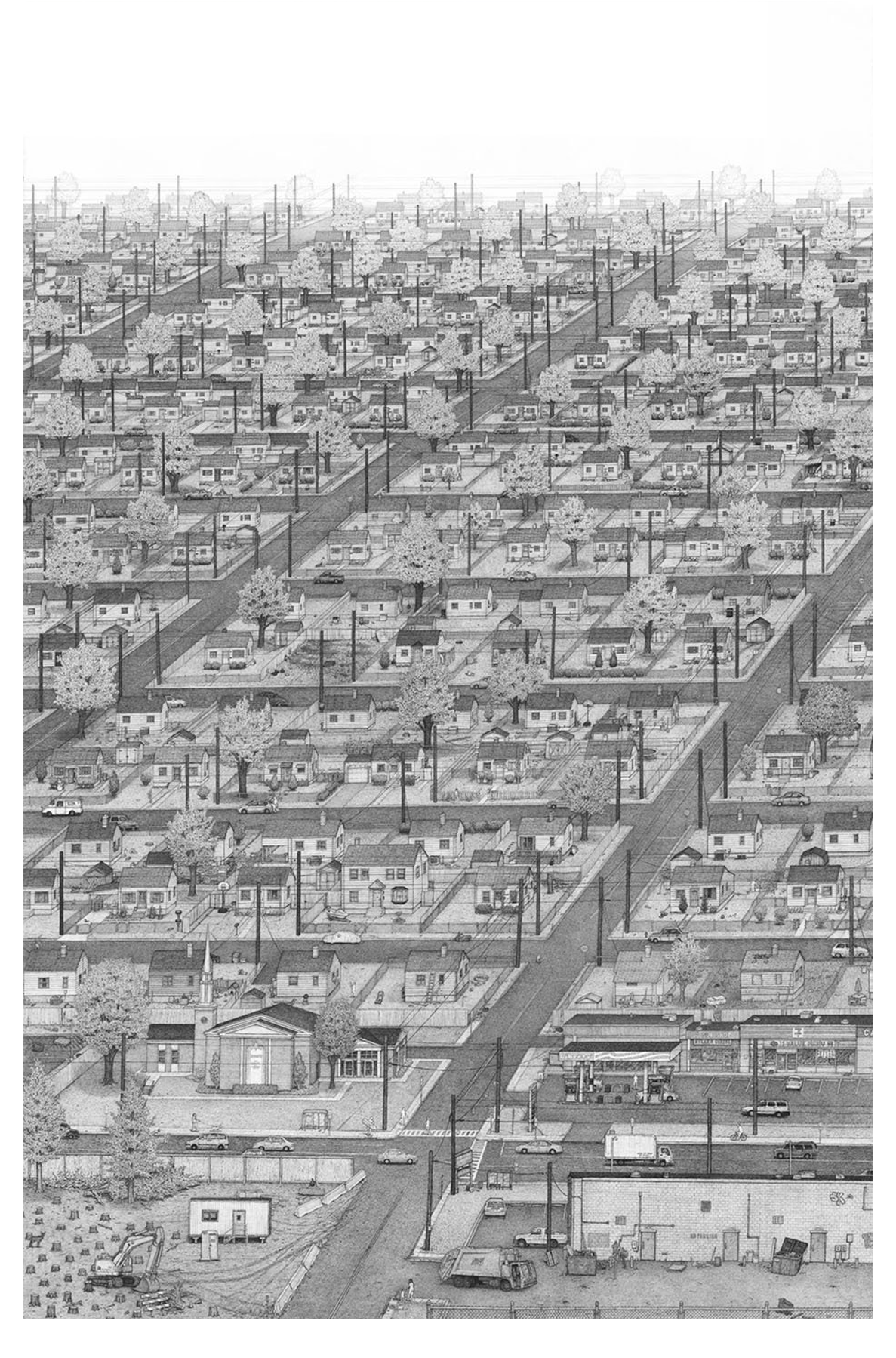

Americana ascribes itself to the lawn. The verdant blades behind the white picket fence. The home beyond with a happy nuclear family inside. The lawn laid out empty over their empire. Unused and remembered only by the timer of the sprinkler system. The suburban lawn is a wasted use of land. It is devoid of life other than sod and squirrels.

The lawn in its traditional, rural context is idyllic. Rolling hills mowed by cattle evoke abundance and power. These hills inspired city-dwellers to build public parks to dwell in the grass as a communal space. In an impotent attempt to emulate those spaces for singular owners, suburbia became characterized by the lawn. Unfortunately, scale perversion reduces the lawn to a few hundred square feet. This tiny, overly manicured space renders the power of the endless green useless. The benefits of vast, open land is subsequently abandoned.

Strangely, suburbanites seem to unconsciously refuse to occupy the front lawn of their 2,400 square foot estate. Despite the money poured into maintaining a front lawn’s appearance, witnessing a human spending time on that lawn is remarkably rare. Even on a perfect day, you’ll find manicured lawn after manicured lawn with a soul delighting in one seldom seen. This underscores the fundamental hypocrisy of suburbia: at its root, it is a lifestyle for those more interested in mediocre wealth signaling than developing genuine bonds with the community in which they live.

Worse still, one cannot overstate how incredibly wasteful a lawn is. They may be installed cheaply, but much like vinyl siding, seem to constantly require more time and money to upkeep. Trimming, weeding, and fertilizing are labor-intensive and often require specialized products. The lawn’s existence is artificially maintained regardless of the amount of chlorophyll produced. These resources are a bad investment long term and show thoughtlessness concerning the full life cycle of a property.

Peculiarly, the grasses that bring the most pride were not developed for this land or climate. America grew unique grasses, but colonizers brought their homeland’s grasses with them for ease of understanding. These invasive species exterminated the native flora and forever altered the fauna. The historic strength of those European grasses fed cattle and in turn the populace. Now, they feed no one. Their claim to existence on this continent is now near purely aesthetic. At the price of our ecology, that aesthetic deserves to be questioned ruthlessly.

What is the alternative to this landcover? What is better than half-dead, drought-ridden bluegrass? That should depend entirely on your location. According to the US EPA, North America has 182 Level III ecoregions, for which locally defining characteristics can be identified. Let better understanding the ecoregion you occupy guide you. Learn what the soil beneath your feet is. What minerals in it best support which plantings. Awareness of place-ness is a prerequisite to responsibly basking in its glory.

If you’re west of the Balcones Fault line, like El Paso, your lawn might look like a rock garden dotted with Torrey Yucca (Yucca faxoniana) and lizards baking in the dry heat5. People delight in rock gardens that are sculptural and create a processional space of repose. They’re an aesthetic indulgence of land I can steadfastly get behind, but exclusively due to the backbone of respect for their ecology. An extreme climate like the Chihuahuan Desert is uncompromising, as such it forces most inhabitants to bow to its will, only sheltering what was meant to survive. Jumping through the hoops to avoid the climate in El Paso would be perpetual nonsense. That is how you should conceptualize any deviation from the native ecology: perpetual nonsense.

If you’re in a more tolerant region, such as Houston’s swampland, other options, albeit inappropriate to the climate, become a possibility. Still, they should be paid no mind. Something that can survive well here may be poison within the span of a few years, besides being contextually inappropriate. Let’s re-imagine the Houston lawn as a detention basin fenced-in with Big Muhly (Mulhenbergia lindheimeri), and when dry, blooming with Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). A detention pond is low cost and creates space for the floodwater that otherwise would be forced to fill your home when the next relentless storm strikes. That’s a great investment. Further, Big Muhly is such a fluffy treasure to gaze upon as it blows in the wind and Swamp Milkweed is a leading host plant for Monarch Butterflies, whose habitats are currently threatened. These layers of repair create beauty and restore simultaneously. This is a lawn that lets nature occupy it, even when you don’t.

I implore you to think about the ecological concerns your region faces and actively fight them. Find the ways to harbor life on your lawn. Who’s endangered? What’s invasive? How can you be hospitable to the former and wary of the latter?

Houston, June 14, 2020

I really enjoyed this piece. We forget the spaces we own isn’t just our eco system. Encouraging new life in our own spaces.

This really is informative and well written! good job

Loved your thoughts on this topic and especially the suggestions you gave for lawn alternatives. But what about local ordinances on lawn upkeep and guidelines? I feel like lawns were an easy way to soften hard lines & architecture, hence why they are literally everywhere in suburbia.

Thank you, Faisal. I think of the local ordinances for property maintenance similarly to zoning due to their common legal background to protect property values. I do agree that suburbia generally likes the idea of beautification of their abominable little McMansions, as this allows them to display further wealth; however, the way suburbanites integrate the natural beauty falls flat when they’re being so wasteful with regard to the natural ecosystem. Simply put if you have to irrigate something, it was not meant to grow where it’s been put. It’s absolutely ugly and harsh to replace a thriving biome with one that first, was only long ago associated with wealth, and second, actively destroys the native landscape. There are better ways of softening the hardness of architecture. The most beautiful landscape architecture is a synthesis of what the ecosystem needs, aesthetics, and functional goals (like hiding bad architecture).

As an aside, local lawn ordinances get inforced in some really strange ways and the tactics to resolve these issues disproportionately target residents of low income. Take for example the story of Gerry Suttle, the octogenarian woman who in 2015 had a warrant issued for her arrest after an unkempt lawn: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/boys-mow-lawn-to-keep-elderly-texas-woman-out-of-jail/

It is very problematic to live in a place that fines and arrests another person who is financially unable to maintain their property. Particularly, if the reason to do so exclusively roots in the selfish protection of one’s own wealth.

The only thing a lawn is good for, is for asking people to get off of it.

Bailey, this is very funny and gets right to the heart of suburban property ownership mindset. A showcase of “look what I have, and it’s not yours!”

This is an intriguing post, and calls out a sort of unspoken guilt among many lawn-‘owners’ (myself included). To that end, the resources you provide are really helpful. Thinking more deeply about all this, I do think that, despite the history of privileged suburbia, there are many ways to understand the complex desires at the ‘root’ of the American lawn. The desire may go beyond the midcentury ideal of a white, middle class American Dream, and become caught up in a sort of long for intimacy with the earth – soil, grasses, milkweed. Quite thought-provoking.