Before composing these thoughts, while reviewing an initial draft, I found myself rising from my desk and meandering around the room, sketching random paths to regain my focus. It seems to me that this type of movement is fundamental to our ability to comprehend the world around us. I wonder if many of the projects we’ve undertaken, before materializing on paper or a computer screen, were originally conceived while wandering through the neighborhoods we’ve inhabited.

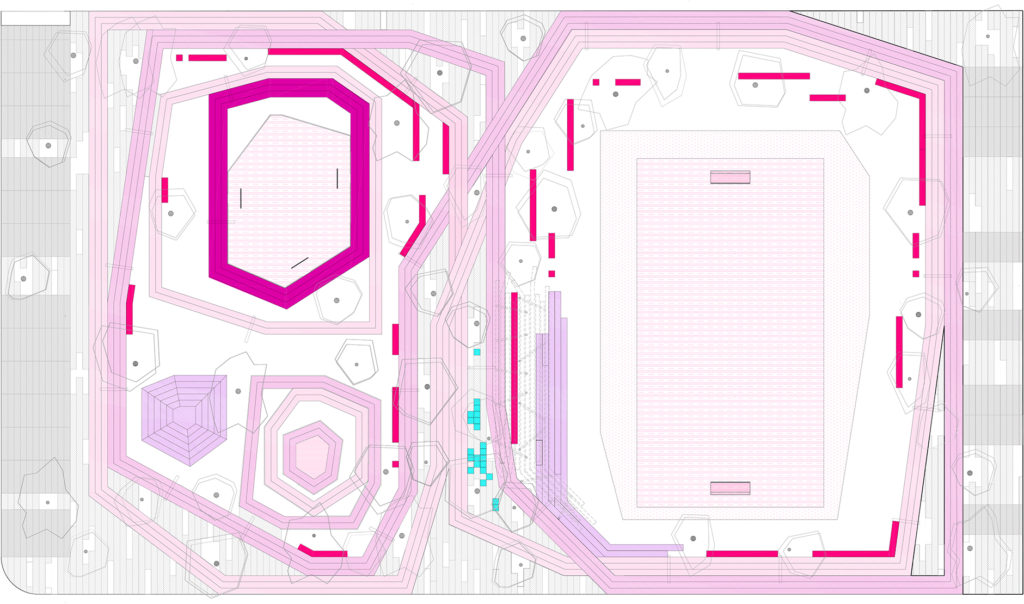

When we initially approached the design of the urban project “Kindergarten Park” (which earned us the first prize in a design competition for strategic urban and architectural concepts within the “Valle de Puebla” Housing Complex plan in Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican State of Baja California), our starting point was observing the imprints left by the activities of local residents on a dusty patch of urban ground. Despite its apparent vacancy, we considered these footprints as evidence that it was already a part of the urban fabric. We decided to retain the name “Kindergarten Park,” given by the neighboring community due to its proximity to a now-defunct kindergarten. We aimed to honor the echoes, rhythms, and patterns we sensed in this seemingly barren space.

We translated our vision into a dynamic strategy, weaving together different scales and conditions much like the lines on a playground floor that reassembled the rings formed by children’s games. These rings contained new play structures and furnishings that encouraged various movement patterns.

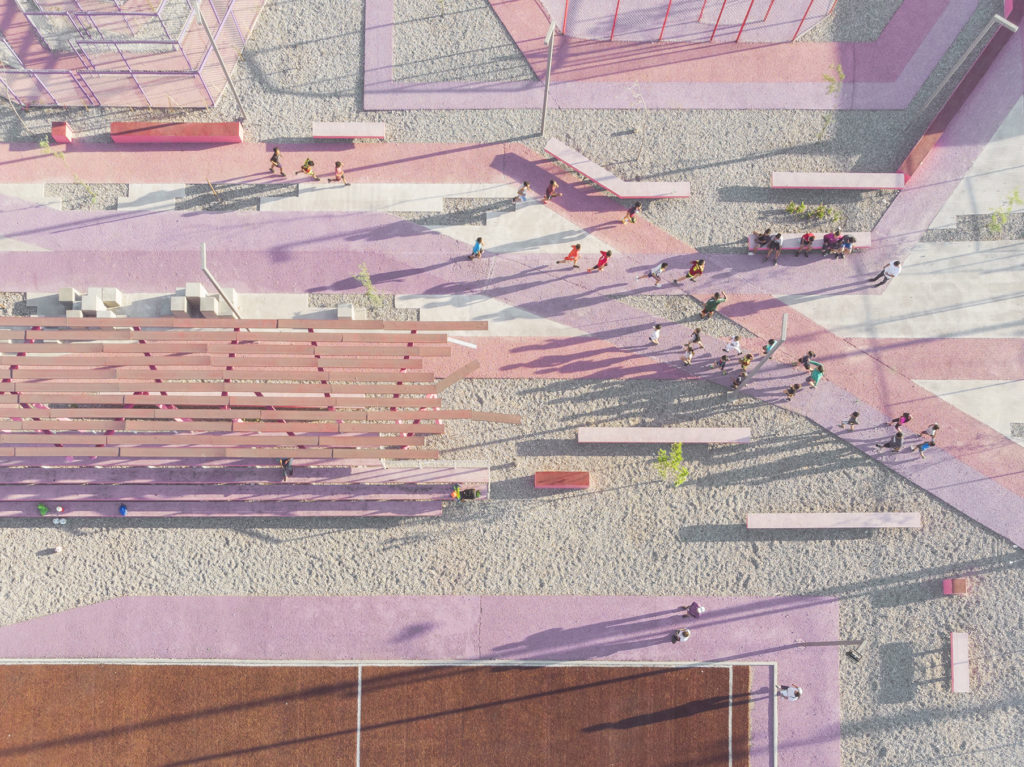

Our proposal responded to the diverse and multidirectional traces of movement suggested by the footprints. Consequently, the contact points between the rings extended to the adjacent streets, encouraging a continuity of urban activity. Shaded by pergolas and trees, this inviting space, complete with stands, transformed into a hub for social interaction with the neighborhood. It allowed for different uses by residents throughout the week.

Our inspiration stemmed from the work of artist Everton Wright, whose “Walking Drawings” create large-scale art on select coastal landscapes, using the British shoreline as his canvas. Various participants leave their mark by etching grooves in the sand through their movements, be it walking or running. In this way, the public becomes active contributors, shaping their own space.

Just as one can witness on the beaches of cities like San Lorenzo Beach in Gijón, Spain, where this splendid natural canvas is available, citizens’ activities are etched during low tide, only to be washed away by the high tide. It’s crucial to remember that in our cities, it’s the citizens who craft the public spaces with their unique life stories. Our city is a tapestry of individual imprints interwoven and overwritten every day, forming a distinctive calligraphy.

“I wanted to take my studio practice into a public space and onto a larger canvas, and so ‘Walking Drawings’ was born. It also allowed me to connect and collaborate more interactively with people.” Everton Wright employs both mechanical resources and hand tools to draw lines, subsequently allowing participants to add their own marks. As architects, we’re entrusted with the opportunity to design public spaces that contribute to turning the collective narratives drawn by many into the language of urban design. Our role is to observe and facilitate rather than dictate. We hold the key to striking the balance between aesthetics, technical and construction aspects, and how users ultimately breathe life into these spaces.

Madrid, September 1, 2023